The Art of the Zaramo Identity

Tradition, and Social Change in Tanzania

Review by: Zachary Kingdon, Tanzanian Affairs

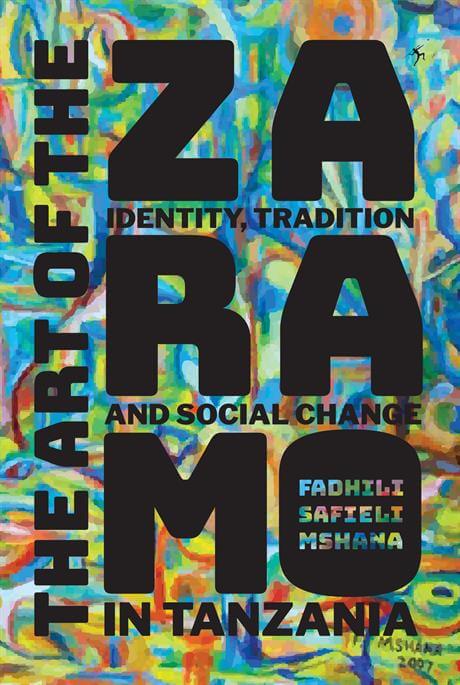

The Art of the Zaramo

Fadhili Safieli Mshana

Mkuki na Nyota’s 2016 edition of The Art of the Zaramo: Identity, Tradition and Social Change is a well-produced (and more affordable) paperback edition of Fadhili Mshana’s doctoral dissertation, which he completed in 1999 with the original title Art and Identity among the Zaramo of Tanzania (State University of New York at Binghamton).

Mshana is a professor of Art History at Georgia College and State Universty in Milledgeville, GA, in the USA. Although he completed his art historical education in Dar es Salaam, East Anglia and the US, Mshana started his career as a school teacher in Tanzania. Not only is he a visual art practitioner himself, he can also claim descent from a venerable blacksmithing lineage, so his identification with Tanzanian artistry runs deep and it is not surprising that his book is written in the voice of a culturally committed Tanzanian.

The Art of the Zaramo follows a standard dissertation format, with the first couple of chapters devoted to situating Zaramo wood carving practices within an historical and sociological framework. But the book also celebrates the resilience of these practices, and their responsiveness to new influences over time, within the rich cultural ‘mix’ of Dar es Salaam and of the wider Uzaramo area. At its core the book presents three themed essays on three respective forms in the Zaramo sculptural corpus. The first themed essay, on mwana hiti trunk figures, is presented in Chapter Four and deals with the way these remarkable, stylised, ritual artworks have retained their relevance as foci for female identification and articulation of female potency within the changing parameters of Zaramo female initiation rites. The second essay on figurative grave markers is covered in Chapter Five and discusses the role that widespread cultural change has had on memorial practices, focusing especially on the impact of the spatial and ideological upheaval instituted as part of the ‘villagisation’ programme which underpinned Tanzania’s post-Independence socialist policies. Mshana seems to suggest that the continuing survival and variety of figurative memorial sculptures in a context of spatial upheaval and, latterly, in contexts of proliferating cultural choices, is linked to the personalised forms of honouring ancestors and the continuing strength of family and ancestral ties. Chapter Six incorporates an engaging and enlightening discussion of Nyerere’s canny appropriation of the kifimbo (a short staff widely used by elders in many Tanzanian ethnic groups) to communicate and enhance his political authority.

But following this insightful discussion, Mshana’s cautious conclusion, with his predominantly object-focused approach, appears to leave more questions than answers on issues such as how individual Zaramo sculptors in Tanzanian contexts responded to new influences and experiences and how their artworks may accrue complex biographies and take on significances beyond the original contexts of their creation.

The Art of the Zaramo makes a welcome contribution to the field of East African art studies, but it can be over-cautious in places and sometimes seems averse to engaging in theoretically-informed interpretive analysis in favour of making ‘safe’ (p. 158) pronouncements that avoid, rather than engage with, complex realities. There is also relatively little in the way of direct Zaramo voices or voiced experiences in the book. Indeed ‘the Zaramo’ are referred to throughout as a homogenous block inhabiting an undifferentiated ‘Zaramo lived reality’

(p. 154). The author also defaults to other forms of generalisation at times and frequently seems to invest concepts of ‘modernity’ and

‘modernisation’ with active historical agency rather than human actors. Similarly, the author’s concepts of ‘tradition’ and ‘identity’

remain unspecified and un-problematised, which leaves them open to Frederick Cooper’s critique of being ‘putative’ and too ambiguous for

rigorous analysis (Colonialism in Question, 2005, pp. 59-60). Finally, this reviewer cannot help noting that Mshana’s book perpetuates an

old bias in African art studies in considering only the art of wood sculpture as a worthy object for study in a book about The Art of the

Zaramo. Zaramo women’s ceramic arts are not considered in the book and other creative forms, like the commercialised blackwood genres, for

example, are only briefly discussed.

Zachary Kingdon

Zachary Kingdon is Curator of the African Collections at National Museums Liverpool. He conducted his doctoral research among Makonde sculptors in Tanzania and holds a PhD in Advanced Studies in Non-Western Art from the University of East Anglia. He is the author of A Host of Devils: The History and Context of the Making of Makonde Spirit Sculpture (Routledge, 2002). He also coedited East African Contours: Reviewing Creativity and Visual Culture (HornimanMuseum, London, 2005).