Robert Berold

Deep South, South Africa

Deep South was started in 1996 by Paul Wessels and Robert Berold [who took over as sole owner/publisher from 2004]. Our aim was to publish what we considered to be innovative and risk-taking South African poetry, regardless of market limitations. Innovation and depth continue to be the main criteria in the decisions to publish.

March 2020

How did you get into editing poetry?

In 1989 I was invited by chance to edit New Coin, and did for 10 years. It was an established poetry magazine (founded in 1965 and still thriving today), and in the 1980s it had quite an English-department bent. South African poetry was then (as now) divided into different compartments and subcultures, not knowing much about each other or their different aesthetics. At the time I was reading across many genres of 20th century international poetry. I was particularly impressed by America a Prophecy, an anthology of US poetry edited by Jerome Rothenberg and George Quasha, which included poetry from the edges of literature – sermons, songs, fragments, chants, schizophrenic utterances, as well as poetry from a range of standard and non-standard US poetics. I wanted to find the same range of poetries in my own country and print the most vibrant examples of each genre I could find.

The reading and editing involved was a real education for me, in both literature and politics. The 1990s was a particularly fertile period for South African poetry. Poets met the coming of democracy with excitement and with apprehension. Some of them (Rampolokeng, Sole, Nxumalo, Motsapi) saw immediately that the political deals being made were bound to distort the freedoms they had fought for, and wrote about “the shame of this sham-change” (as Rampolokeng put it). Because everything was unprecedented, poets took risks, and there was much exploration, innovation and diversity of form. New Coin became an arena where these poets and their poems could speak to one another. It was a community of sorts, it was certainly so for me. I travelled and met poets, published interviews with them, and organised some performance gatherings. Deep South is a continuation of that in a way.

What led you to set up Deep South?

Seitlhamo Motsapi, one of the truly original voices in New Coin, had told me that his first manuscript had been turned down by

publishers. I was so outraged by this that my response was to offer to publish it myself. I approached my friend Paul Wessels, who was

running a mail order bookshop called Deep South Distribution, and he had experience in book design. We called our press Deep South: Paul

did the design and print management, I worked with the poets, editing their manuscripts. Our first book, Motsapi’s earthstepper/the

ocean is very shallow,

was politically defiant, pan-African, highly suspicious of the democratic transition, embracing mystical poems written in a stately

biblical voice, some poems almost surreal, others satirical with sardonic puns and inventive misspellings. It is surely one of classics

of post-apartheid poetry.

Seitlhamo Motsapi, one of the truly original voices in New Coin, had told me that his first manuscript had been turned down by

publishers. I was so outraged by this that my response was to offer to publish it myself. I approached my friend Paul Wessels, who was

running a mail order bookshop called Deep South Distribution, and he had experience in book design. We called our press Deep South: Paul

did the design and print management, I worked with the poets, editing their manuscripts. Our first book, Motsapi’s earthstepper/the

ocean is very shallow,

was politically defiant, pan-African, highly suspicious of the democratic transition, embracing mystical poems written in a stately

biblical voice, some poems almost surreal, others satirical with sardonic puns and inventive misspellings. It is surely one of classics

of post-apartheid poetry.

Paul and I worked in partnership for a few years, producing books by Motsapi, Ari Sitas, Joan Metelerkamp and Khulile Nxumalo. After that I continued Deep South on my own. I also edited a number of poetry manuscripts for other publishers.

What criteria do you follow when bringing authors to your list?

My criteria are intuitive and subjective. Ultimately I can only publish work I feel to be engaging and moving. I’m biased towards image, viscerality, physicality, musicality, plain language, and old-fashioned modernism. I’m not too concerned about the market. I know that

some poets will have very limited sales because they will be considered difficult or confrontational – but I don’t mind. I try to take a

long view, publishing books that I think people will still want to read in 20 (or 50) years’ time. There aren’t too many books like

that, and the two or three I do each year are quite enough for me.

viscerality, physicality, musicality, plain language, and old-fashioned modernism. I’m not too concerned about the market. I know that

some poets will have very limited sales because they will be considered difficult or confrontational – but I don’t mind. I try to take a

long view, publishing books that I think people will still want to read in 20 (or 50) years’ time. There aren’t too many books like

that, and the two or three I do each year are quite enough for me.

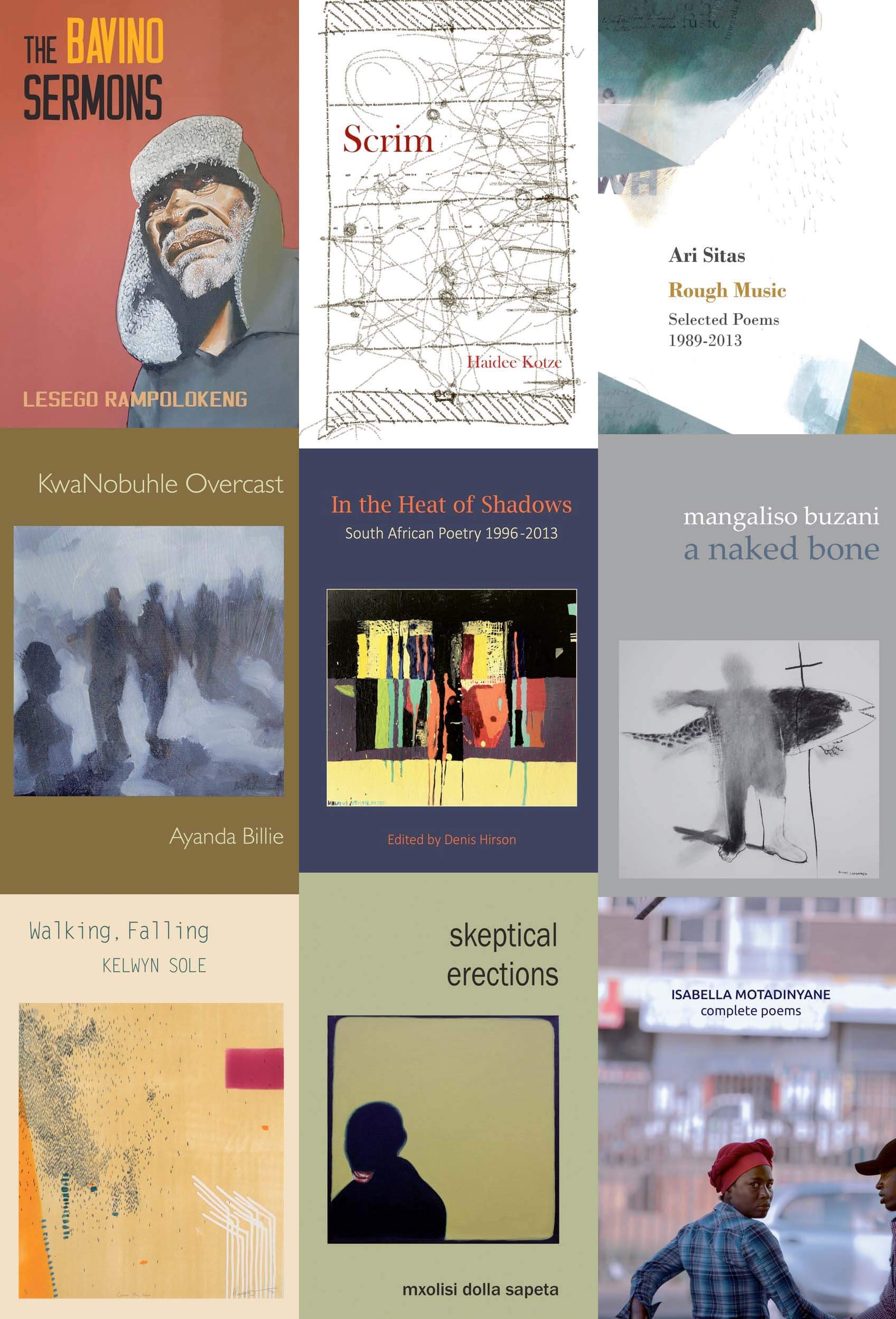

Recognition of Deep South books has been slow, but recent literary awards have helped: Kobus Moolman A Book of Rooms (Glenna Luschei Prize for African Poetry 2015), Lesego Rampolokeng Bird-Monk Seding (UJ Prize 2018), Kelwyn Sole Walking, Falling (SALA Poetry Award, 2018), and Mangaliso Buzani a naked bone (Glenna Luschei Prize 2019).

Did you begin with poetry and add novels to the repertoire, or were you always interested in publishing different genres?

I really want to stick to poetry. The few novels I’ve published were written by poets or poetical in their structure and language.

Has politics always been a part of what South African writers have explicitly engaged with?

Well yes, that is unavoidable – apartheid was like Nazism, a brutal invasion of the lives of black people at every level. With some exceptions, white people supported it, or tried to ignore its contradictions, but it corroded all of our lives and our minds. Thank god racism is not explicitly legal any more. But we are in the era of intensified capitalism, with its corruption and hyper-consumerism and growing inequality in which the poor are still black. At the same time we are in the grip of the slow tsunami of human extinction by climate change, and all the short-term frenzied behaviour which that leads to. At the same time we are seeing in South Africa the collapse of community. At the same time we live with the fallacies of identity politics and of populism. None of these are fertile contexts for poetry. But poetry is where you find such things being observed and scrutinised. South African poets have done that over the last 30 years, and continue that scrutiny right now. To paraphrase Pound, poetry is still the best place to get the real news.

Would you like to be able

to publish other languages? In the

Heat of Shadows: South

African Poetry 1996-2013

(ed. Denis Hirson) has several poems in translation from Afrikaans, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sesotho and Xitsonga – is

translation an area that Deep South would like to explore?

Would you like to be able

to publish other languages? In the

Heat of Shadows: South

African Poetry 1996-2013

(ed. Denis Hirson) has several poems in translation from Afrikaans, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Sesotho and Xitsonga – is

translation an area that Deep South would like to explore?

I want to keep to English and the South African variations of English, which expand its expressive range tremendously. Yes, I definitely want to publish translations. It will be slow process, as there is hardly any tradition of poetry translation from African languages here, especially translations that are also convincing as poems in English. Deep South has commissioned a book of contemporary isiXhosa poetry by Eastern Cape poets.

Over the 20+ years that Deep South has been operating, how have you responded to the technological changes, from the advent of the Internet to the digitisation of texts?

Digitisation has made production of books a lot easier, with more flexibility of design and no need for long litho print runs. Otherwise I’m way behind, with no social media presence, and e-books only thanks to African Books Collective.

Do you have recommendations of other writers we should be looking out for?

There are some wonderful poets in South Africa who deserve to be much better known. Just to take some published recently by Deep South – Mangaliso Buzani, Alan Finlay, Angifi Dladla, Haidee Kotze/Kruger (also published by Modjaji), Isabella Motadinyane (a revised version of her collected poems first published by Botsotso), Dolla Sapeta, Ayanda Billie. I have been impressed by recent books by Vangile Gantsho, Musawenkosi Khanyile, Busisiwe Mahlangu, Colleen Crawford Cousins. Each of these poets (and I can think of others) has a unique language which integrates music, politics, love, despair, and spirituality.

What ambitions do you have for Deep South over the coming years?

Just to keep editing and publishing books that really mean something; that is, books that make readers see the world and themselves differently. I also want to bring other people into running Deep South. As you know, it is almost impossible to make a poetry press sustainable without donations of time and money.

How does your practice as a poet affect your day-to-day activities as a publisher? Do you juggle other roles alongside your writing life?

Editing, publishing, teaching creative writing – these can nourish one’s life as a writer. But when they pull your creative energy too far into the writing of others, these activities become a burden, and resentment can follow (this has happened to me to some extent, I’m extricating myself slowly and deliberately). On the other hand brilliant new writing invigorates one’s own writing practice. We need literary communities, especially in a country like ours which is close to illiterate in its reading of imaginative literature. I’m part of a local reading group that meets weekly to read South African and international poetry. If literary communities don’t exist, we can create them.