Nick Mulgrew

uHlanga, South Africa

uHlanga is South Africa's progressive poetry press. Founded in 2014

as an annual magazine of poetry from KwaZulu-Natal, uHlanga now focuses on publishing debut anthologies from the country's most

promising young poets.

May 2019

Jatinder Padda (JP): uHlanga began as a magazine in 2014, but is now a book publisher. What led to the decision to set up a publishing press?

Nick Mulgrew (NM): It just wasn’t going to work out commercially as a magazine. We published one issue with poets from my home province of KwaZulu-Natal, and although it broke even, I figured it made more economic sense to publish single-author collections. I also believed single-author collections could make more of a cultural impact — a belief that I think has been borne out.

JP: You have new and established poets on your list – how do you entice them to join uHlanga?

NM: Frankly, I think just existing as a poetry publisher in southern Africa is enough of an enticement for many people. There are always way more poets than avenues for publication, especially in print, and double especially in good-looking print. But, to answer in a less stuck-up way, I try to be open with my authors. Each book is a partnership, and a personal relationship. I think that counts for something.

JP: Do you see a variety of poetic practices in the submissions you receive? Spoken word is having quite a moment, so do you see some of that on the page as poets submit?

NM: In our last submissions period we received over 120 manuscripts, in a combination of five languages. I’ve seen almost everything, from photobooks, to books being part of musical projects, to poetic practices that are stuck in time half a century ago in terms of subject and approach. Spoken word has always been present in modern South African poetry, I just think we’re paying a bit more attention to it because of certain successful books written by spoken word poets. What’s exciting, though, is how spoken word practice is evolving into a textual practice. There’s a lot of concrete poetry going around, with spoken word techniques being typographically represented, or represented through other playful means. Not that all of it is good, but it is really cool to see.

JP: The books are also beautifully designed and varied in their covers – do you use the same designers? Is there a particular process by which designers spend time with the poems?

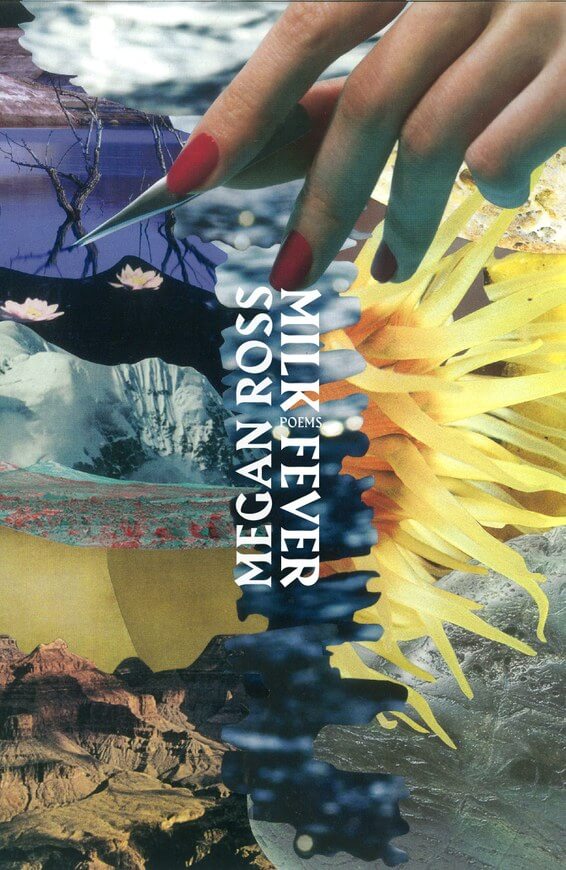

NM: I art direct everything with regard to uHlanga, so I’ll take that compliment with much gratitude. I design all the

covers myself, with photographs, art, and other images coming from varied sources, usually made in some sort of collaboration with the poet,

or someone who is mutually known by me and the poet. I try to keep it within a circle of known quantities. For example, my wife designed the

uHlanga logo, a university friend did the collage for Megan Ross’s Milk Fever, and Liminal’s cover was painted by the

poet’s sister. Working like that is as much about practicality as aesthetics: however limited, you just have to use the resources at your

disposal.

NM: I art direct everything with regard to uHlanga, so I’ll take that compliment with much gratitude. I design all the

covers myself, with photographs, art, and other images coming from varied sources, usually made in some sort of collaboration with the poet,

or someone who is mutually known by me and the poet. I try to keep it within a circle of known quantities. For example, my wife designed the

uHlanga logo, a university friend did the collage for Megan Ross’s Milk Fever, and Liminal’s cover was painted by the

poet’s sister. Working like that is as much about practicality as aesthetics: however limited, you just have to use the resources at your

disposal.

JP: How does the wider arts and cultural community in South Africa affect uHlanga and the South African poetry community? Also, how do you see uHlanga in the context of other young South African poetry presses, of which there are now a few?

NM: I’m not sure how to answer these questions, because the only thing I’m concerned with, with regard to uHlanga, is making good books. The influence of the cultural and artistic communities of South Africa comes out in the poems, which then feedback into those communities to whatever degree. I see a wider appreciation for poetry now, but that’s perhaps just the fault of my perspective, growing into my role as a participant in the poetry space in South Africa, and seeing up close how people are interacting with it. It’s probably better a question for other young poetry publishers, like vangile gantsho (impepho press) or Michéle Betty (Dryad Press), to answer about how uHlanga fits in our collective context.

JP: I note that in your recent submissions call out, poetry in Southern African languages (alongside English) were requested.

Can you see a time when you come to publish as many non-English poetry collections as English? And if so, what are the challenges and

opportunities?

NM: Man, I hope so. We asked for manuscripts in three languages other than English, and we got some really exciting work that I hope to publish. I don’t see a time where I myself publish as many books in, say, isiZulu and isiXhosa as we do in English, because uHlanga is a one-person operation and my editorial expertise lies in English. That’s also where the market is right now, despite many publishers’ attempts to change it. Bookstores (and how they imagine the market to be) are the biggest challenge. It doesn’t matter how many great books we publish in languages other than the dominant English and Afrikaans if people don’t stock them and sell them. I don’t know if I’m the person to change it, even if I could change it. It requires a collective effort from as many individuals trying to affect similar changes.

JP: How do you see South African poetry in the continental context? And further, how important are global markets for your poets?

NM: Thanks to the lingering effects of apartheid, South Africa is still really isolated, I feel, from many parts of the continent. We’re a young and arrogant country, and I think our arrogance gives other Africans pause, and keeps us at a distance. That’s just what I’ve observed, though. We have more to learn from publishers and poets in other African countries than we have to teach them, especially surrounding the questions of distribution development, cross-continental collaboration, and building a reading culture that isn’t just enjoyed by the privileged.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, global markets are the most lucrative avenue for South African publishers and poets to go down, not just because our local reading market is so small, but because of exchange rates and the perception of prestige, even within South Africa, that these markets provide. If someone wants to have a solid go at making at least part of their living from poetry, they need to focus outside South Africa, particularly in markets in the northern hemisphere. It’s a horrible reality, but it’s one that’s shared, I think, throughout the Global South.

JP: Have you any recommendations of upcoming poets to watch, either at uHlanga or other presses?

NM: We’re bringing out the debut of Musawenkosi Khanyile in a few months, called All The Places, and it’s just brilliant. What’s particularly special about it — other than the quality of the writing and its poetic meta-narrative — is that some of Musa’s first poems were published in that one issue of the uHlanga magazine I talked about earlier. That publication helped him start his journey to getting his MA in Creative Writing, during which he wrote this book. It feels like the closing of a circle, and fills me with joy.