Colleen Higgs

Modjaji Books, South Africa

Modjaji Books was started in 2007 by Colleen Higgs, it is an independent press that publishes the writings of Southern African women. Colleen talks to Stephanie Kitchen about running an independent feminist press in South Africa.

January 2019

Stephanie Kitchen (SK): Modjaji Books is a medium-sized South African publisher of books mainly in fiction, short stories, poetry, translation and biography categories. Can you tell us a bit more about the publisher’s origins, name and aspirations?

Colleen Higgs (CH): Modjaji is actually a tiny publisher that ‘punches above its weight’.

I started Modjaji Books in 2007 as an independent feminist press that publishes southern African women’s fiction, poetry, and biography mostly. Modjaji fills a gap by providing an outlet for writing by women that takes itself and its readers seriously. For a small press, Modjaji Books is visible and vibrant and has offered a good platform for the writers we’ve published.

Modjaji answered a series of needs and issues for me and more broadly. My daughter was about to start primary school and I wanted to be there for her, which is not easy if you work in a corporate or civil service environment. As a writer I was keenly aware of the gatekeeping that keeps women’s writing out of sight. I worked at the Centre for the Book in Cape Town for seven years, researching how the world of publishing works from the outside and had done a little publishing while working there. I’d also self-published my own collection of poetry, Half Born Woman, as an experiment in small-scale publishing. I felt ready to take on the challenge.

SK: You have built up an impressive list of books over the past ten years or so (a snapshot is available here). What are the books you are proudest to have published?

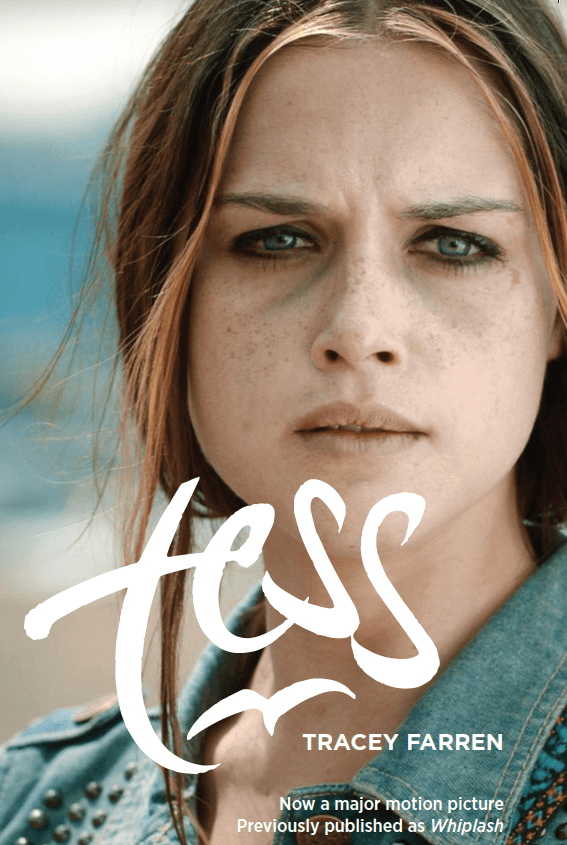

CH: I’m proud of all our titles, but some books have a bigger story as to why we published them. Some of the titles that jump to mind

immediately are Whiplash/Tess; Invisible

Earthquake, Reclaiming

the L Word; Grace; Bom

Boy; Flame

and Song, A

to Z of Amazing South African Women.

The reasons are varied; I will share some of them. Whiplash by Tracey Farren because I loved the writing, I felt a jolt of electric

energy when I read the book, and because it is the book that lead me to start Modjaji Books in the first place, as a proper publishing

company and not as a thing I did on the side. Also it challenged ideas of what could be successfully published and later a movie was made, Tess,

which led us to republishing a movie tie-in edition. Invisible Earthquake because it was about stillbirth and a mother’s grief,

something that at the time was not widely written about. Barbara Boswell’s Grace, beautifully written, prize-winning title about

the effects of domestic violence. Reclaiming the L-Word was life-changing for many of the contributing lesbian writers; Zanele

Muholi allowed us to use one of her photographs for the cover, it was an important book to bring stories of lesbians’ lives into the

mainstream.

CH: I’m proud of all our titles, but some books have a bigger story as to why we published them. Some of the titles that jump to mind

immediately are Whiplash/Tess; Invisible

Earthquake, Reclaiming

the L Word; Grace; Bom

Boy; Flame

and Song, A

to Z of Amazing South African Women.

The reasons are varied; I will share some of them. Whiplash by Tracey Farren because I loved the writing, I felt a jolt of electric

energy when I read the book, and because it is the book that lead me to start Modjaji Books in the first place, as a proper publishing

company and not as a thing I did on the side. Also it challenged ideas of what could be successfully published and later a movie was made, Tess,

which led us to republishing a movie tie-in edition. Invisible Earthquake because it was about stillbirth and a mother’s grief,

something that at the time was not widely written about. Barbara Boswell’s Grace, beautifully written, prize-winning title about

the effects of domestic violence. Reclaiming the L-Word was life-changing for many of the contributing lesbian writers; Zanele

Muholi allowed us to use one of her photographs for the cover, it was an important book to bring stories of lesbians’ lives into the

mainstream.

I’ve also been delighted by the wonderful opportunities that have arisen for a number of writers as a result of having a well-received book published. Invitations to the Edinburgh Festival (The Blacks of Cape Town), a trip to the US for a prize-giving for Reneilwe Malatji for Love Interrupted; a movie made out of the book (Whiplash/Tess), a trip to Brazil after we sold the rights there (Futhi Ntshingila for Do Not Go Gentle). An opera made out of one of Wame Molefhe’s short stories from Go Tell The Sun. Not to mention that most writers have received invitations to literary festivals, developed relationships and networks with other writers and readers.

SK: Several of Modjaji Books have won prizes. Can you tell us a bit about the prize-winning books and the difference such recognition has made? What is your view of literary prizes – in South Africa, in the African continent and globally?

CH: Bom Boy won a prize and was short-listed for two important prizes. We have now sold world English rights to Bom Boy to Catalyst Press in the US. After the success of Bom Boy, Yewande Omotoso was able to get a UK agent and her second book was bought by several publishers and has also been successful. Whiplash was also short listed for several prizes, one of which meant the book was stocked in stores that had refused to stock a book about a street prostitute before. Tracey Farren also secured a UK agent and has had her next two books sold internationally – Catalyst Press bought Snake also published by Modjaji. And her third book has been bought locally by Kwela. The media success of Tjieng Tjang Tjerries and other stories brought the author, Jolyn Phillips, to the attention of Human & Rousseau, an imprint of the biggest local publishing company. They then published her first collection of poems in Afrikaans, and after winning major local awards for both her stories and poems, Phillips was invited to work as a lecturer at the University of Johannesburg. She had been working as a teaching assistant at the University of the Western Cape before.

We’ve had an author short-listed for the Caine Prize, Lauri Kubuitsile, for her story published in The Bed Book of Short Stories. She was invited to the UK for the prize-giving in Oxford. Reneilwe Malatji won a US prize for her short stories, Love Interrupted, also published in the US subsequently. Prizes can mean increased sales; universities and schools sometimes prescribe these titles. For example, these are some of the titles that have been prescribed: Running & other stories by Makhosazana Xaba, Bom Boy, The Blacks of Cape Town, Reclaiming Afrika edited by Zethu Matebeni.

SK: Outside South Africa, Modjaji Books is perhaps best known as the original publisher of Born Boy by Yewande Omotoso (2011), winner of the South African Literary Award for First Time Published Author, and shortlisted for other prizes. The book is now being published in the United States and the author’s second work (The Woman Next Door) was published to international acclaim. What did the prizes and subsequent global success of the book mean for the author, and for you as the publisher?

CH: I think you should probably ask Yewande this question. However, I am aware of the following – she has become one of South Africa’s best-known and well-respected writers of the younger generation of writers. She has had opportunities to write at a number of different residencies. She has made a fair bit of money out of her second book, The Woman Next Door, I would guess, which has also paid for time for her to write. She has done quite a bit of mentoring work all over Africa.

Yewande’s success has probably meant more for her than Modjaji, but it has strengthened Modjaji’s credibility as a discerning publisher, both locally and internationally.

SK: I understand that Modjaji Books publishes exclusively women writers. What led you to that decision?

CH: I wanted to offer a platform for women writers, in particular Black women writers who would be unlikely to be published by more commercial publishers. Modjaji is meant to be true to the spirit of Modjadji the rain queen, a powerful female force for good, growth, new life and regeneration.

We have been able to publish books by women that don’t fit into clear commercial genres – Hester Van der Walt’s Hester se Brood (Hester’s Book of Bread), for example, is about making bread and a memoir of living in a small village in the Karoo with her life partner. Many people loved it because she writes wonderfully, and includes her partner’s beautiful drawings; other publishers wouldn’t touch it because it was too eclectic.

We’ve also published slim volumes of short stories (and memoirs), that are 20,000 words, even less. Mainstream publishers, if they even touch short stories, not to mention debut collections expect them to be at least 40,000 words. Generally in South Africa, if short stories are published, they would be by writers who have already got a name for themselves. I think Modjaji might be almost the only publisher that takes a risk on a debut collection of stories. In my experience women writers experiment with form, and sometimes that means shorter manuscripts, that are deep and powerful. I’m thinking here of Karen Lazar’s Hemispheres, about her experience of having a massive stroke at 39. Reneilwe Malatji’s collection, Love Interrupted, a darkly humourous collection of short stories has been hugely successful, but would not meet the word length criteria of most publishers here.

SK: You have written that the history of publishing in South Africa is enmeshed with the culture of resistance. Women’s voices, particularly Black women’s voices, are marginalised globally. Black women’s voices are still marginalised in South Africa. How do we understand it that Black women’s voices are underrepresented or ignored in an African country?

In the 12 years that Modjaji has been publishing there has been a big shift. However, I still think that women writers are not taken quite as seriously here, like elsewhere in the world, as they might be. The discussions you read about Vida, the Bechdel test, articles in the Guardian, etc., these are still issues here. So far in South Africa only white writers have been awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, Nadine Gordimer and JM Coetzee. Also in-depth reviews, interviews, articles in prestigious magazines focus on men, and prize recipients are still overwhelmingly white and male, although I haven’t taken the time to do a Vida-like count.

Things have shifted considerably since Modjaji started 12 years ago and there are many more Black women being published now by most of the relevant publishers. The proportion to population in the country is still low. It has to do with South African history and power politics, and who makes decisions. Modjaji was a pioneer, providing a home for fresh new women’s voices that couldn’t access or had been rejected by the mainstream publishing houses. It was also crucial for me that this was foregrounded as Modjaji’s mission.

Now there’s a publisher who publishes only Black writers – men and women. Modjaji Books has definitely contributed to the urgent sense that we need to hear from women writers and in particular Black women writers.

SK: Do you sense change in the literary establishment? What about in academic writing where the barriers Black women face are arguably even greater?How do you see Modjaji Books’ and other activist publishers’ roles in challenging this?

CH: I am not an expert on academic writing and publishing, so can’t comment on that. Yes there is a change in the literary establishment. I think Modjaji was at the cutting edge of this. But many factors have come into play including influences from the US and other parts of the world, such as the women’s marches, #metoo, #blacklivesmatter and identity politics.

Modjaji is a feminist press. And that’s to do with what’s going on in the world. Having lived through and enacted it, I think publishing only women writers is a hugely political act, particularly if you think about the way publishing is owned, media is owned, who gets to make the decisions, and how women are represented. Even in South Africa, where we have a progressive constitution, lesbians are violently attacked and in some cases murdered simply for their sexuality; all women live with fear of violence and abuse, and our rape statistics are horrific.

Women do have a different experience of the world – not just because they are women, but because of the way power is structured and filtered. There was a point, not so long ago, where married women couldn’t open a bank account in South Africa, without permission from their husbands – married women were treated as minors.

SK: Do you have a sense of the audience or readership of your books – in South Africa and elsewhere?

CH: Something of a sense, but not a detailed sense. I know that because of African Books Collective all of our titles for which Modjaji

receives international rights are bought by many of the most prestigious US and other academic libraries. We sometimes get emails from

international readers.

Some of our titles are available for free on Worldreader’s mobi project. For example, My First Time: Stories of sex and sexuality from women like you has been read more than 1.5 million times.

SK: You are also known as a writer, poet and activist besides your work as an editor and publisher for Modjaji Books. Many editors also write, or want to write, but how in your case does this combination work in practice? I’m thinking for example of how your own practice might enable you to better engage and empathise with the authors you publish; at the same time, editors and publishers do sometimes need to employ critical distance and sometimes take very practical-based tough decisions. How do you see these relationships between writing, literature and publishing?

CH: I became interested in publishing because I am a writer myself. And I do understand, I guess, in a slightly more empathetic way, what it’s like to be a writer. And what it’s like to be a woman in this world and industry. I don’t know that the biases are always entirely conscious, but they are there.

I’ve experienced enormous generosity towards me and towards Modjaji Books from a range of people: friends, writers, readers, feminists, booksellers, book fairs, book activists, librarians, other publishers, the media.

I’ve had to learn to become objective to the process of publishing, I think at first I thought I could be friends with all the writers Modjaji has published, and that they understood Modjaji’s enterprise and extreme limitations, but I have gotten into several very difficult situations, because of cash flow and money problems, and a lack of capacity to manage all the different functions of the press, especially as it has grown to having published well over 120 titles.

My own writing has been somewhat sidelined, as I have put all my creative energy into Modjaji, and into publishing and promoting the work of other writers. I did it willingly, but would like to step back a little over the coming years and take some of my creative energy back for myself.

SK: As a writer, editor and publisher, I would like to ask you a question about language. Modjaji Books publishes mainly in English, but occasionally also in Afrikaans and you also publish translations. What is your approach to language in a country with several official languages and a complex linguistic history? Is it possible (economically) or desirable (culturally) for South African publishers to be publishing in languages other than the dominant/cultural elite language of English?

CH: In retrospect, I think it has been a mistake for me to publish in languages other than English. Although I read Afrikaans and can speak it, I don’t have enough of an in-depth knowledge of Afrikaans, and even less so of the one African language that I learnt to speak as a child, Sesotho. As the publisher, I can’t make judgement calls, and this has also got me into some awkward situations. However, I do love the books I’ve published and am glad they got to exist. I think at least two of them would not have been published without Modjaji.

Yes, English is what it is, in terms of power dynamics, colonial legacy, etc; but it is for publishers other than me to take on local languages and to publish in them. English does have the value in South Africa of being a lingua franca here and internationally. But publishing in English means you are also ‘competing’ to be heard by readers who could choose to read any of the other books in the world published in English.

SK: We met at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2018 where there was a special focus on African publishing Programme Lettres d’Afrique: changing the narrative’, I understand you also participate in the International Alliance of Independent Publishers. How important are such ‘international’ connections and opportunities for the work of Modjaji Books? Are the gains commercial, cultural, or both?

CH: Yes, international connections are important, not so much for commercial reasons, but to have one’s work validated in a sense, to learn about the industry and how it is similar and different in other countries. Sometimes these connections leads to rights sales and although so far these bring in a relatively small amount of money, it is good for authors to feel their work has a wider readership, and sometimes it brings opportunities for them to travel too.

I have learnt so much from my friends in the Alliance about bibliodiversity, about being a courageous publisher, about trends in different markets and have felt enormous support from them. I look forward to going to Frankfurt each year to see my publishing friends from all quarters of the world, to be inspired, to be ‘seen’ and to be reminded of the importance of the work.

SK: Colleen, you are also an advocate of small scale independent publishing. You wrote A Rough Guide to Small Scale and Self-publishing in 2005 and also publish regular editions of the African Small Publishers Catalogue which includes publishers from across the African continent. Could you give us a sense of all this self-publishing activity, literary practice and activism? How are you building networks among small presses? How do you see the value of this – for authors, editors and booksellers?

The Catalogue has been a limited way to bring small publishers together, it has allowed information sharing, as has the Facebook group Book Publishing in Africa, for which I am one of the moderators. The South African Book Development Council currently arranges for small presses to attend and participate in the SA Book Fair. Small presses gain visibility through their presence in the Catalogue. And other parts of the book world can find them. We do have a Publishers’ Association in South Africa, PASA, so publishers who are part of that don’t need what the Catalogue has to offer in the same way. I’ve always tried to share information as much as I can within my limits, as information is valuable. Some of this has included sharing information about opportunities such as invitation programmes for book fairs, ways to source funding, and so on. I also share information for writers, less so than at first, I’m just too busy now to do much of it.

I’ve found the Frankfurt Book Fair is a wonderful place to meet small press publishers from Africa and other parts of the world, and is a space to share challenges and come up with solutions.